Frida Kahlo: A Feminist Icon Who Defied Gender Norms

Table of Contents

Frida Kahlo: A Feminist Icon Who Defied Gender Norms. She remains one of the most iconic artists of the 20th century, a figure whose influence transcends the boundaries of art, culture, and politics. She was more than just a painter; she was a storyteller who used her canvas as a mirror to reflect her experiences, struggles, and triumphs. Her work resonates deeply because it speaks to the universal human conditions of pain, love, resilience, and identity. Kahlo’s art is not merely visual—it is deeply emotional, autobiographical, and symbolic. She painted her reality, one shaped by physical suffering, heartbreak, and an unwavering commitment to expressing her innermost thoughts. Her paintings are filled with symbolic elements that offer insights into her psyche, often blending surrealism, Mexican folk traditions, and deeply personal iconography.

Born in 1907 in Coyoacán, Mexico, Kahlo grew up in a country undergoing a profound transformation. The Mexican Revolution was in full swing, and its effects shaped her early worldview. She later claimed 1910 as her birth year, aligning herself with the revolutionary movement that sought to redefine Mexican identity. This strong sense of nationalism and cultural pride became integral to her personal and artistic expression. From an early age, she was exposed to art and intellectual discourse, influenced by her father’s profession as a photographer and her mother’s indigenous heritage.

Kahlo’s life was punctuated by adversity. At six years old, she contracted polio, which left her right leg thinner than her left. This early battle with illness was just a precursor to the more profound physical trauma she would experience later in life. As a teenager, she was involved in a catastrophic bus accident that left her with multiple fractures in her spine, pelvis, and legs. The accident not only ended her dreams of becoming a doctor but also left her in chronic pain for the rest of her life. Confined to her bed for months, she turned to painting as a means of self-expression and survival. With a mirror positioned above her, she began a series of self-portraits that would define her artistic career. Through art, she found a way to narrate her suffering, turning pain into beauty, and isolation into introspection.

Frida Kahlo’s work is characterized by a unique blend of surrealism, realism, and indigenous Mexican influences. While many critics attempted to categorize her as a surrealist, she rejected this label, famously stating, “I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.” Her paintings often depicted her personal struggles, with images of broken bodies, wounded hearts, and symbolic elements representing her emotions. Some of her most renowned works, such as The Two Fridas, The Broken Column, and Henry Ford Hospital, showcase her unfiltered approach to self-exploration.

Beyond art, Kahlo was an outspoken political activist. She and her husband, the famed muralist Diego Rivera, were staunch communists who supported workers’ rights and indigenous pride. Their home, La Casa Azul, became a gathering place for leftist intellectuals, revolutionaries, and artists. She maintained friendships with figures like Leon Trotsky and was deeply involved in the Mexican Communist Party. Her political beliefs were reflected in her art, which often incorporated themes of nationalism, anti-imperialism, and resistance.

Kahlo’s personal life was as tumultuous as her art. Her relationship with Diego Rivera was marked by deep love, artistic collaboration, and repeated betrayals. Rivera’s infidelities, including an affair with Kahlo’s own sister, caused her immense pain. In response, she engaged in her own extramarital affairs with both men and women, challenging traditional notions of gender and sexuality. Despite their separations and reconciliations, Rivera remained one of the most significant influences in her life and career.

While she was relatively unknown outside of Mexico during her lifetime, Kahlo’s fame grew exponentially after her death in 1954. Today, she is celebrated as a feminist icon, a pioneer of self-expression, and a symbol of resilience. Her face is emblazoned on murals, fashion, and popular culture, while her art continues to be studied and admired globally. Frida Kahlo was not just an artist—she was a movement, a revolutionary force whose legacy continues to inspire.

This essay explores the many facets of Frida Kahlo’s life, from her early struggles and artistic evolution to her political activism and cultural impact. By examining her experiences and works, we gain a deeper understanding of why she remains such a compelling and enduring figure in contemporary art and feminist discourse.

The Life-Changing Accident

On September 17, 1925, Frida Kahlo’s life took a devastating turn when the bus she was traveling on collided with a streetcar in Mexico City. The accident left her with catastrophic injuries: her spine was fractured in three places, her pelvis was crushed, and a metal handrail impaled her abdomen, causing severe internal trauma. The impact shattered her right leg in multiple places and dislocated her shoulder. Doctors were initially unsure if she would survive, and her recovery required months of immobility, numerous surgeries, and the use of a full-body cast. This experience marked the beginning of a lifetime of chronic pain and medical complications, ultimately shaping the way she perceived herself and the world around her.

During her lengthy convalescence, Kahlo turned to painting as a means of both self-expression and emotional survival. Bedridden and unable to move freely, she used a specially constructed easel and a mirror placed above her bed to create her earliest self-portraits. Her injuries and forced isolation allowed her to delve deeply into her psyche, resulting in artwork that reflected themes of suffering, resilience, and self-identity. Her paintings became an outlet for her frustration, anguish, and resilience, laying the foundation for the artistic themes that would define her career.

The accident not only altered her body but also redirected her ambitions. Prior to the collision, she had dreams of becoming a doctor, a career path she had pursued rigorously at the National Preparatory School. However, with her body forever changed, she abandoned these aspirations and committed herself entirely to painting. The trauma she endured became an essential part of her artistic narrative, with her work serving as both documentation and catharsis for her lifelong suffering.

Related Paintings:

- Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress (1926) – One of her first self-portraits, created during her recovery, showcasing her early artistic style.

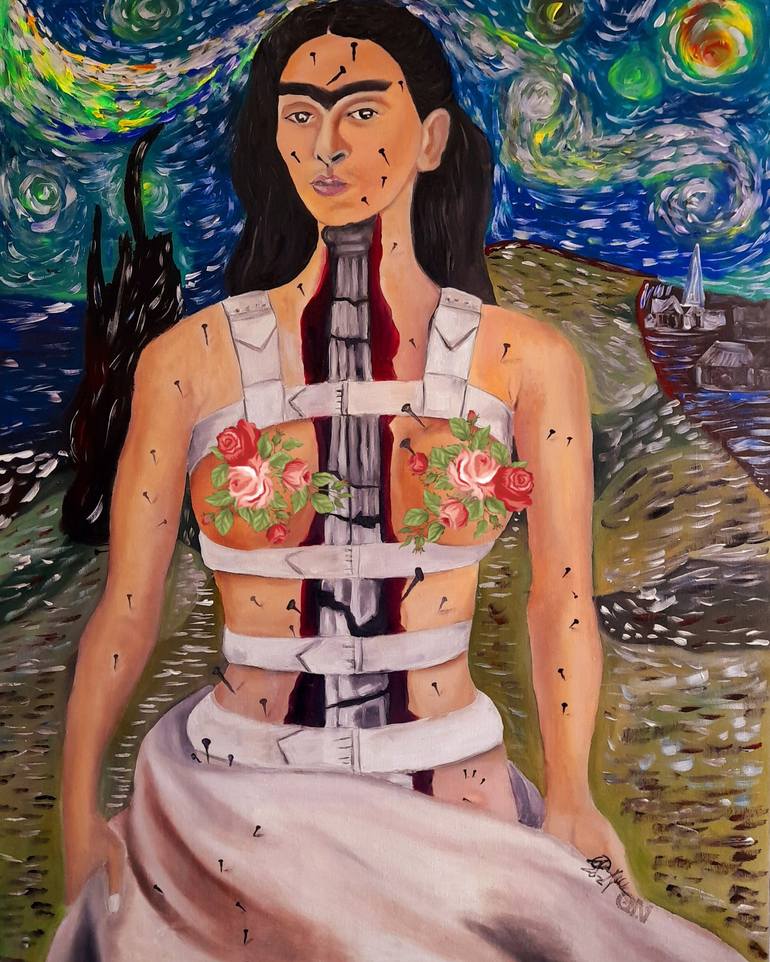

- The Broken Column (1944) – A raw depiction of her physical pain, showing her body split open with a crumbling column replacing her spine.

- Henry Ford Hospital (1932) – Illustrates her experience with medical trauma, reflecting her multiple surgeries and miscarriages.

Matilde Calderón: Frida Kahlo’s Mother and Her Influence

Frida Kahlo’s mother, Matilde Calderón, played a significant role in shaping the artist’s worldview and personal struggles. A devout Catholic of indigenous and Spanish descent, Matilde upheld strict religious beliefs and adhered to traditional Mexican values. Her perspective on womanhood, faith, and duty deeply influenced Frida’s early upbringing, fostering both a sense of admiration and rebellion in her daughter.

Matilde was known for her strong discipline, ensuring that her children adhered to Catholic morals and traditional family expectations. This created an early tension for Frida, who was naturally independent and curious about political and philosophical ideas that diverged from her mother’s teachings. Matilde’s emphasis on religious devotion and self-sacrifice clashed with Frida’s emerging feminist ideals, leading her to question the rigid roles assigned to women in Mexican society. This conflict can be seen in Kahlo’s later works, where she often depicted themes of suffering, martyrdom, and female resilience through religious iconography. You can read more about the impact of toxic mother-daughter dynamics.

Despite their differences, Matilde provided Frida with a deep connection to Mexican folk traditions, a theme that would permeate her artwork. Frida’s love for Tehuana dresses, vibrant colors, and indigenous symbolism can be traced back to her mother’s cultural pride. However, Matilde’s strict expectations for Frida to conform to traditional femininity and marriage expectations contributed to her daughter’s struggles with identity and self-worth. Frida’s defiance of gender norms and her embrace of bisexuality and political radicalism were in many ways a reaction against her mother’s conservative values.

Matilde’s approach to suffering and endurance also left a lasting impression on Frida. Raised in a household where sacrifice was expected, Frida internalized the idea of enduring pain as a sign of strength. This belief became a defining aspect of her art, as she often portrayed herself in states of agony yet imbued with resilience. Her paintings, such as My Birth (1932), explore themes of maternal influence, religious guilt, and the tension between life and death—ideas likely rooted in her mother’s teachings.

Though their relationship was fraught with tension, Matilde Calderón’s beliefs left an indelible mark on Frida’s identity and artistic expression. Whether she was embracing or rejecting her mother’s values, Kahlo continuously engaged with these themes in her work, solidifying her position as an artist who both honored and challenged her heritage.

Related Paintings:

- My Birth (1932) – A surreal depiction of childbirth, symbolizing Frida’s complex relationship with her mother.

- Henry Ford Hospital (1932) – Explores themes of motherhood, loss, and suffering.

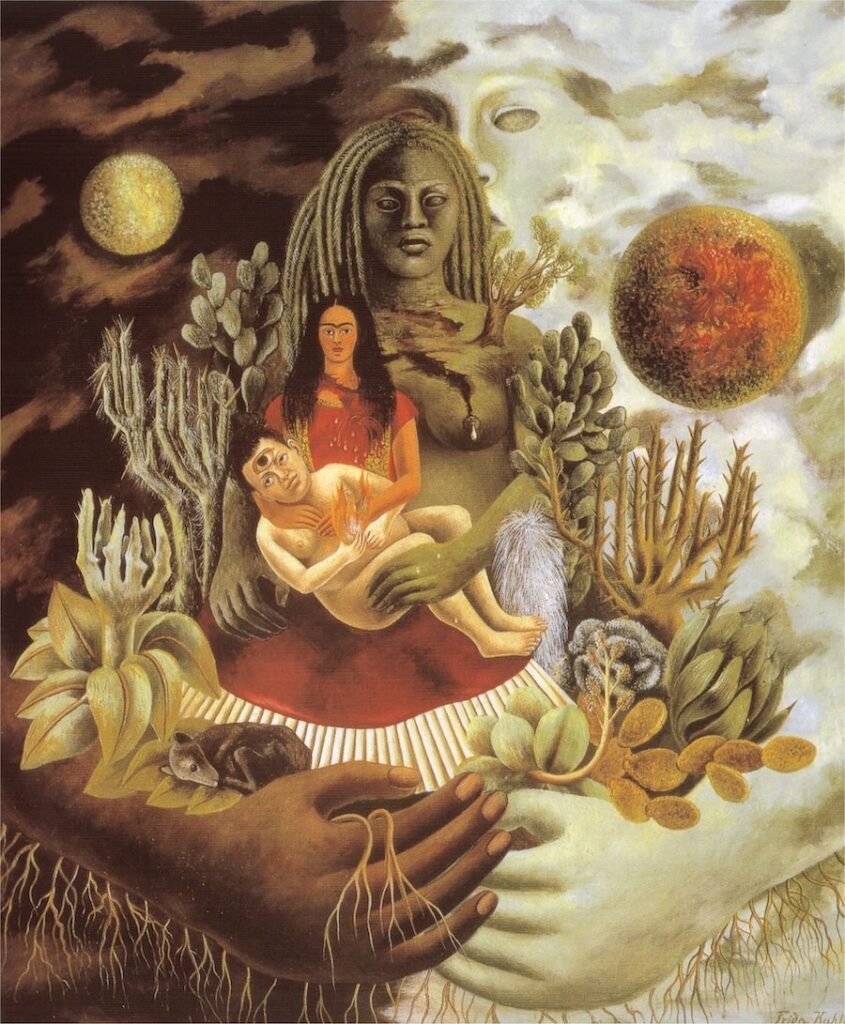

- The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth, Myself, Diego, and Señor Xólotl (1949) – Incorporates maternal imagery and cosmic symbolism.

Frida and Diego Rivera: Love and Turmoil

Frida Kahlo’s relationship with Diego Rivera was as passionate as it was tumultuous. She met Rivera in 1928 when she was 21, and he was already a well-established muralist, twice her age. Their love was immediate and intense, and despite warnings from friends and family about Rivera’s notorious infidelity, they married in 1929. Rivera encouraged Kahlo’s artistic development, praising her unique perspective and subject matter. He introduced her to Mexico’s artistic and political circles, elevating her profile within the art world. Their relationship was as much a partnership of creativity as it was of romance, influencing each other’s work deeply.

However, their marriage was marred by Rivera’s numerous affairs, including one with Kahlo’s younger sister, Cristina. This betrayal devastated Kahlo, intensifying her emotional suffering and deepening the themes of heartbreak in her paintings. In response, Kahlo engaged in affairs of her own, with both men and women, including Leon Trotsky and the Mexican singer Chavela Vargas. Despite their infidelities and conflicts, they shared a profound and enduring bond, one that kept them emotionally intertwined even during periods of separation.

Their marriage was one of extremes—deep affection and admiration counterbalanced by fierce arguments and betrayal. They divorced in 1939 but remarried a year later, unable to stay apart. Their relationship continued to be complex, with Kahlo’s deteriorating health and Rivera’s ongoing affairs adding further strain. Despite everything, Rivera remained by her side in her final years, taking care of her when she became bedridden.

Kahlo’s paintings during their marriage often reflected her emotional turmoil. The Two Fridas (1939), painted during their divorce, represents two versions of herself—one heartbroken and European-dressed, the other proudly Mexican, holding Rivera’s portrait. Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) is a powerful declaration of independence following their split, with Kahlo depicted in a masculine suit, her hair cut short, rejecting traditional femininity.

Though deeply painful, her relationship with Rivera was instrumental in shaping her as an artist and individual. He was both her greatest supporter and her greatest source of agony. Their love was unconventional, filled with both artistic admiration and personal betrayal, but it undeniably fueled some of Kahlo’s most profound work.

Related Paintings:

- The Two Fridas (1939) – A visual representation of her heartbreak during her divorce from Rivera.

- Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) – Symbolizes her defiance and transformation after her separation from Rivera.

- Diego and I (1949) – Highlights the emotional pain caused by Rivera’s infidelity, with his face appearing on her forehead as a constant presence.

Art as a Reflection of Pain and Identity

Frida Kahlo’s art is an unfiltered reflection of her physical suffering, emotional anguish, and personal identity. Her paintings serve as a visual diary, where every stroke conveys the weight of her experiences. Unlike many artists who sought to escape reality through their work, Kahlo confronted her pain head-on, transforming it into raw, powerful imagery. She used her body as the primary subject of her paintings, depicting herself with exposed wounds, medical braces, and surrealist elements to illustrate the depth of her suffering.

Her self-portraits are among her most iconic works, providing a direct window into her state of mind. The Broken Column (1944) is a striking example, portraying her body split open, revealing a shattered column in place of her spine, with tears streaming down her face. This painting encapsulates her chronic pain and the fragility of her physical state. Similarly, Henry Ford Hospital (1932) depicts her miscarriage, with symbolic objects floating around her bleeding body, illustrating her grief over her inability to bear children.

Beyond physical pain, Kahlo’s work also explored themes of identity and belonging. As a woman of mixed heritage, she often grappled with questions of cultural duality. The Two Fridas (1939) represents this struggle, showing two versions of herself: one in a traditional Mexican Tehuana dress, the other in a European-style white dress. The painting highlights her internal battle between her indigenous and European ancestry, a theme that recurred throughout her career.

Kahlo’s art was not just personal; it was deeply political. She used her work to challenge gender norms, societal expectations, and patriarchal structures. By openly depicting female pain and sexuality, she paved the way for feminist art movements. Her bold use of symbolism, vibrant colors, and surrealist influences set her apart from her contemporaries, making her one of the most distinctive artists of her time.

Related Paintings:

- The Broken Column (1944) – A haunting depiction of her fractured spine and chronic pain.

- Henry Ford Hospital (1932) – Expresses the trauma of miscarriage and medical intervention.

- The Two Fridas (1939) – Explores dual identity and personal heritage.

- Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) – Represents her suffering and resilience through religious and natural symbolism.

Frida Kahlo: A Feminist Icon Who Defied Gender Norms

Frida Kahlo’s art and life exemplify defiance against the rigid gender norms of her time. She was an artist who unapologetically embraced her own identity, subverting traditional ideas of beauty, femininity, and sexuality. Her work challenged the patriarchal structures of both Mexican society and the broader art world, positioning her as an early feminist icon. Her paintings frequently depicted female suffering, reproductive struggles, and the complexities of womanhood, making her one of the first artists to present these experiences without censorship.

One of the most radical aspects of Kahlo’s persona was her rejection of conventional beauty standards. She deliberately emphasized her unibrow and mustache, refusing to conform to Western ideals of femininity. Her clothing choices also carried political and gendered messages. While she often adorned herself in vibrant Tehuana dresses to honor her indigenous roots, she also posed in men’s suits, embodying an androgynous aesthetic that blurred the lines between male and female identities. Her 1940 painting, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, illustrates this defiance—after separating from Diego Rivera, she painted herself in a loose-fitting men’s suit, with her signature long hair cut short, signifying both personal and artistic autonomy.

Kahlo’s paintings also depicted female pain and the physical challenges unique to women, topics that had long been considered taboo. Henry Ford Hospital (1932) portrays her miscarriage, with her bleeding body surrounded by symbolic objects representing motherhood, loss, and fertility. Her raw and unfiltered portrayal of the female experience laid the groundwork for feminist artists of later generations, who would continue to explore themes of bodily autonomy and reproductive rights.

Additionally, Kahlo was openly bisexual, engaging in relationships with both men and women, including the famous singer Chavela Vargas. Her rejection of heteronormative constraints further cemented her as a trailblazer for gender and sexual fluidity. She painted many strong and independent women, celebrating female relationships and the intimate bonds between women.

Her boldness in addressing issues of identity, gender, and sexuality in her art and personal life has made her an enduring symbol of feminist resistance. Today, her image continues to inspire feminist movements worldwide, proving that her legacy is as relevant as ever.

Related Paintings:

- Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) – A statement of gender defiance and personal transformation.

- Henry Ford Hospital (1932) – A raw portrayal of female pain and miscarriage.

- Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States (1932) – A commentary on cultural identity and the influence of Western ideals on femininity.

Political Activism and Cultural Identity

Frida Kahlo’s political beliefs and cultural identity were deeply intertwined with her art, shaping both her public and private life. She was a staunch supporter of communism, a revolutionary thinker, and a fierce advocate for indigenous Mexican heritage. Her political views were not merely theoretical; they were reflected in her everyday actions, her relationships, and, most significantly, her paintings.

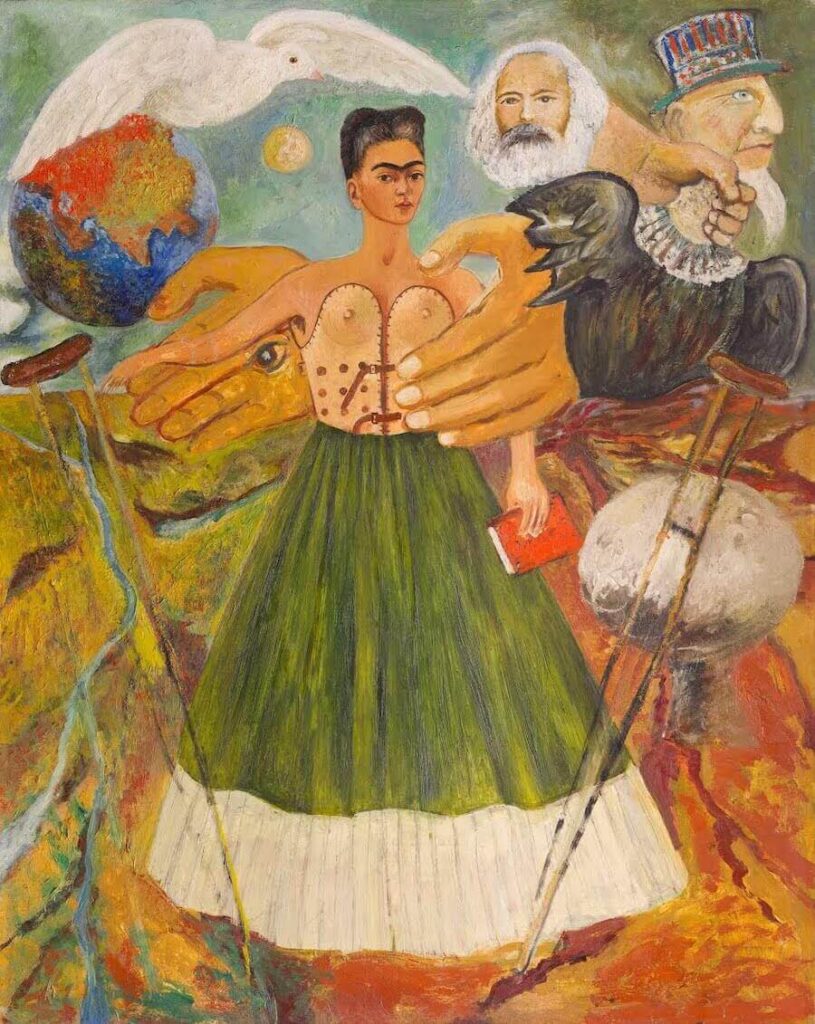

Kahlo and her husband, Diego Rivera, were both committed communists who actively participated in leftist political movements. Their home, La Casa Azul, became a meeting place for radical intellectuals, including Leon Trotsky, who lived there briefly while exiled from the Soviet Union. Kahlo’s alignment with communism was also personal—she saw the struggles of the Mexican working class and indigenous communities as a reflection of her own battles with pain and oppression. Her painting Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (1954) is a testament to her ideological convictions, depicting Karl Marx’s hands providing support and protection.

Beyond politics, Kahlo took immense pride in her Mexican identity. She frequently wore traditional Tehuana dresses, adorned herself with indigenous jewelry, and used pre-Columbian motifs in her paintings. This embrace of Mexicanidad was both a political statement and a personal affirmation of her roots. She rejected European beauty standards and celebrated the resilience and traditions of Mexico’s indigenous peoples. Her painting Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States (1932) illustrates this divide, contrasting industrialized America with Mexico’s deep cultural heritage.

Kahlo’s identity was also shaped by her belief in the power of art as a tool for revolution. She saw painting as a means of giving voice to the marginalized, challenging oppressive systems, and preserving the stories of those often overlooked by history. Her works often included socialist symbols, revolutionary figures, and references to Mexico’s colonial past. Her final political act, just days before her death, was attending a protest against the U.S. intervention in Guatemala—an act of defiance that underscored her lifelong commitment to political activism.

Frida Kahlo’s political and cultural influence endures today. She remains an icon of resistance, an artist whose paintings speak to themes of national pride, social justice, and the personal as political. Her commitment to her ideals, even in the face of suffering, cements her legacy as one of the most politically engaged artists of her time.

Related Paintings:

- Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (1954) – Symbolizes her faith in communist ideology as a solution to suffering.

- Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States (1932) – Explores her conflicted relationship with industrialization and cultural identity.

- My Dress Hangs There (1933) – A critique of capitalism and American consumerism.

Chavela Vargas and the Women in Frida’s Life

Frida Kahlo’s personal and artistic life was deeply influenced by the women around her. From romantic relationships to profound friendships, she found solace and inspiration in the company of strong, independent women. One of the most significant figures in this sphere was the Mexican singer Chavela Vargas, who later confirmed their romantic involvement. Vargas, known for her passionate ranchera music and unapologetic defiance of gender norms, shared many qualities with Kahlo, making their bond one of deep admiration and mutual understanding.

Kahlo’s relationships with women were often as intense and emotionally charged as her art. She openly embraced her bisexuality at a time when such openness was rare, especially for women. She painted numerous female subjects, often portraying them with admiration, intimacy, and tenderness. Her paintings frequently depicted female bodies in ways that challenged the male gaze, presenting women as powerful, resilient, and autonomous beings rather than mere objects of beauty.

Her friendships with women such as photographer Tina Modotti and writer Dolores del Río also played a significant role in her life. These women were pioneers in their respective fields, breaking barriers much like Kahlo did in the art world. Their intellectual and political discussions, as well as their mutual support, strengthened Kahlo’s resolve to create art that was both deeply personal and universally revolutionary.

In her later years, as her health deteriorated, Kahlo leaned heavily on the support of her female friends and lovers. She documented many of these relationships in her diary, writing about her longing, affection, and admiration for the women who stood by her. These emotional connections offered her strength during periods of immense suffering, reinforcing the themes of resilience and passion that defined her work.

Her ability to portray female experiences with raw honesty continues to inspire feminist artists and LGBTQ+ communities today. Kahlo’s depiction of women—whether as lovers, friends, or self-reflections—redefined the way femininity was represented in art.

Related Paintings:

- Two Nudes in a Forest (1939) – A sensual and intimate portrayal of two women, often interpreted as a reflection of Kahlo’s relationships with women.

- Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) – Symbolizing a rejection of traditional femininity after a period of personal heartbreak.

- The Love Embrace of the Universe (1949) – Depicting female figures nurturing and supporting each other, symbolizing the power of female bonds.

The Final Years and Death

Frida Kahlo’s final years were marked by deteriorating health, unrelenting pain, and a sense of urgency in her artistic and political pursuits. By the early 1950s, her body, already fragile from her lifelong battle with illness and injuries, began to fail her further. She underwent several surgeries on her spine and leg, spent months in hospitals, and relied on painkillers to cope with her suffering. In 1953, doctors amputated her right leg due to gangrene, a devastating blow that deepened her depression. Despite these hardships, Kahlo remained artistically and politically active, producing some of her most emotionally charged works during this period.

One of the most significant events of her final years was her first solo exhibition in Mexico in 1953. She was so physically weakened that doctors advised her not to attend, but she refused to miss it. Arriving in an ambulance, she was carried into the gallery on a hospital stretcher, defiantly engaging with guests from a four-poster bed placed at the center of the room. This moment embodied Kahlo’s relentless spirit—her refusal to let her pain silence her presence or stifle her artistic voice.

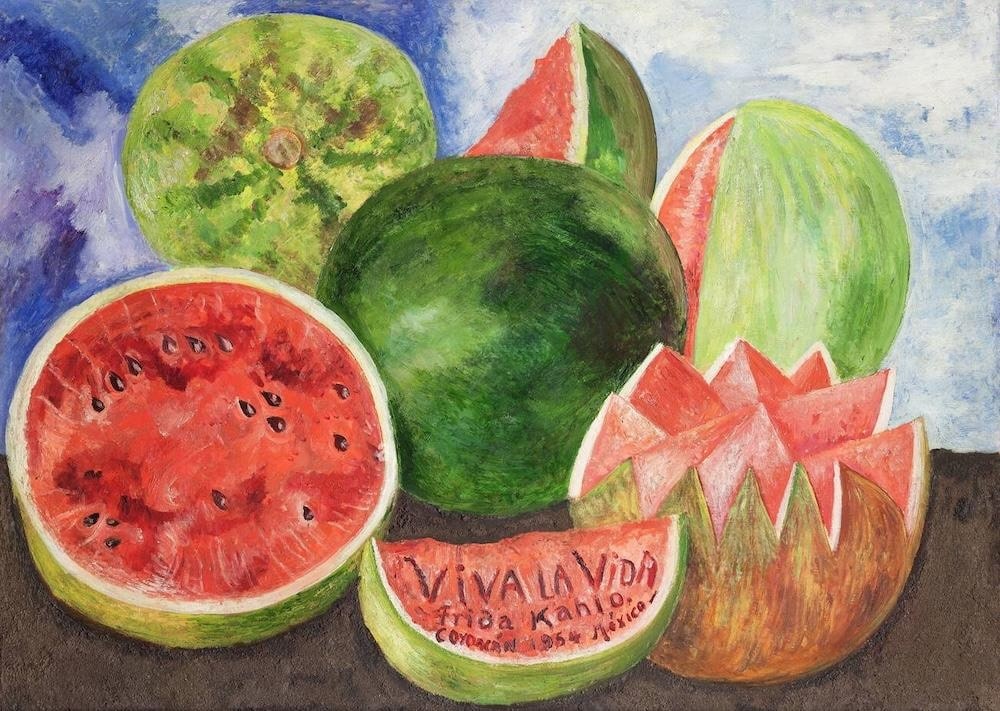

Despite her declining health, Kahlo remained committed to her political ideals. She participated in protests, including one against the U.S. intervention in Guatemala, just days before her death. Her last painting, Viva la Vida (1954), a still life of watermelons inscribed with the phrase “Long Live Life,” reflected a final embrace of existence, even in the face of imminent mortality.

Frida Kahlo passed away on July 13, 1954, at the age of 47. The official cause of death was listed as a pulmonary embolism, but many speculate that she may have intentionally overdosed on pain medication. Her last diary entry reads, “I hope the exit is joyful, and I hope never to return.” Though her physical body succumbed to suffering, her legacy had already begun to take root.

Today, La Casa Azul, her childhood home and the place where she spent her final days, stands as the Frida Kahlo Museum, drawing thousands of visitors who seek to understand the woman behind the myth. Her impact on art, feminism, and cultural identity has only grown with time, ensuring that her presence remains as powerful as ever.

Related Paintings:

- Viva la Vida (1954) – A vibrant still life, symbolizing her acceptance of life and death.

- Frida and the Abortion (1932) – A raw depiction of her struggles with pregnancy loss and mortality.

- Self-Portrait with the Portrait of Doctor Farill (1951) – One of her last self-portraits, showcasing her reliance on medical intervention and her acknowledgment of impending death.

Legacy and Influence

Frida Kahlo’s impact on art, feminism, and popular culture has grown immensely since her death in 1954. Once overshadowed by her husband, Diego Rivera, Kahlo is now considered one of the most influential artists of all time. Her ability to merge personal pain with cultural identity, feminism, and political activism has made her a beacon of resilience and self-expression. Over the decades, Kahlo has become a symbol of empowerment, inspiring movements advocating for women’s rights, LGBTQ+ visibility, and decolonization in art.

Her legacy is preserved through La Casa Azul, her childhood home turned museum in Mexico City, which attracts thousands of visitors each year. The museum houses her paintings, personal belongings, and diaries, offering an intimate look at her life. The Diary of Frida Kahlo, published posthumously, provides further insight into her thoughts, struggles, and creative process, solidifying her voice beyond her visual works.

Kahlo’s influence extends into fashion, literature, and film. Her distinctive aesthetic—Tehuana dresses, elaborate jewelry, and braided hair adorned with flowers—has been widely replicated, turning her image into a recognizable cultural icon. Designers such as Jean Paul Gaultier and Dolce & Gabbana have referenced her style in their collections, celebrating her unique fusion of indigenous and modern elements.

Her paintings remain some of the most valuable and sought-after artworks today. Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) and Diego and I (1949) continue to be auctioned for millions, demonstrating the increasing appreciation of her work. Beyond the art world, her face appears on murals, protest banners, and merchandise, demonstrating her lasting relevance.

In 2002, the film Frida, starring Salma Hayek, introduced her story to an even wider audience, garnering critical acclaim and deepening public interest in her life. She has been the subject of numerous biographies, exhibitions, and retrospectives, further cementing her status as a revolutionary figure.

Today, Kahlo’s legacy endures because she spoke to universal human experiences—pain, love, struggle, and self-acceptance. She transformed suffering into art, creating works that resonate across generations and cultures. She remains an icon of defiance, proving that art can be deeply personal while also carrying global significance.

Related Paintings:

- Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) – Represents her resilience and personal struggles.

- Diego and I (1949) – A reflection on love, obsession, and pain in her relationship with Rivera.

- The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me, and Señor Xólotl (1949) – Symbolizing unity, motherhood, and the interconnectedness of existence.

Epilogue

Frida Kahlo lived a life that burned brightly with passion, suffering, and artistic brilliance. She defied conventions, shattered taboos, and painted a reality that many dared not acknowledge. She embraced her flaws, her wounds, and her identity without compromise, turning her pain into something eternal—an art form that transcends time and place.

Her voice, once confined to the intimate pages of her diary and the strokes of her brush, now echoes across generations. Kahlo’s influence is no longer restricted to museum walls; it lives in the feminist movements she inspired, the LGBTQ+ communities that see their struggles reflected in her defiance, and in every individual who finds courage in their suffering.

Frida Kahlo’s legacy is not simply in the works she left behind, but in the conversations she continues to ignite. Her image, once the representation of a woman in pain, has evolved into a symbol of defiance, strength, and the right to self-expression. She proved that art does not have to conform to rules or fit into rigid classifications—it only needs to be true.

In her final days, Kahlo wrote in her diary: “I hope the exit is joyful, and I hope never to return.” Yet, she never truly left. Her art, her words, and her indomitable spirit remain embedded in the hearts of those who seek freedom from the chains that bind them. Kahlo showed the world that suffering can be transformed into power, that wounds can become art, and that no one—not even death—can silence a woman who has found her voice.

https://www.museofridakahlo.org.mx

https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/diego-rivera-frida-kahlo

https://www.wfmt.com/2018/01/12/frida-kahlo-greatest-love-muse-iconic-lesbian-chanteuse/